Unlearning comics

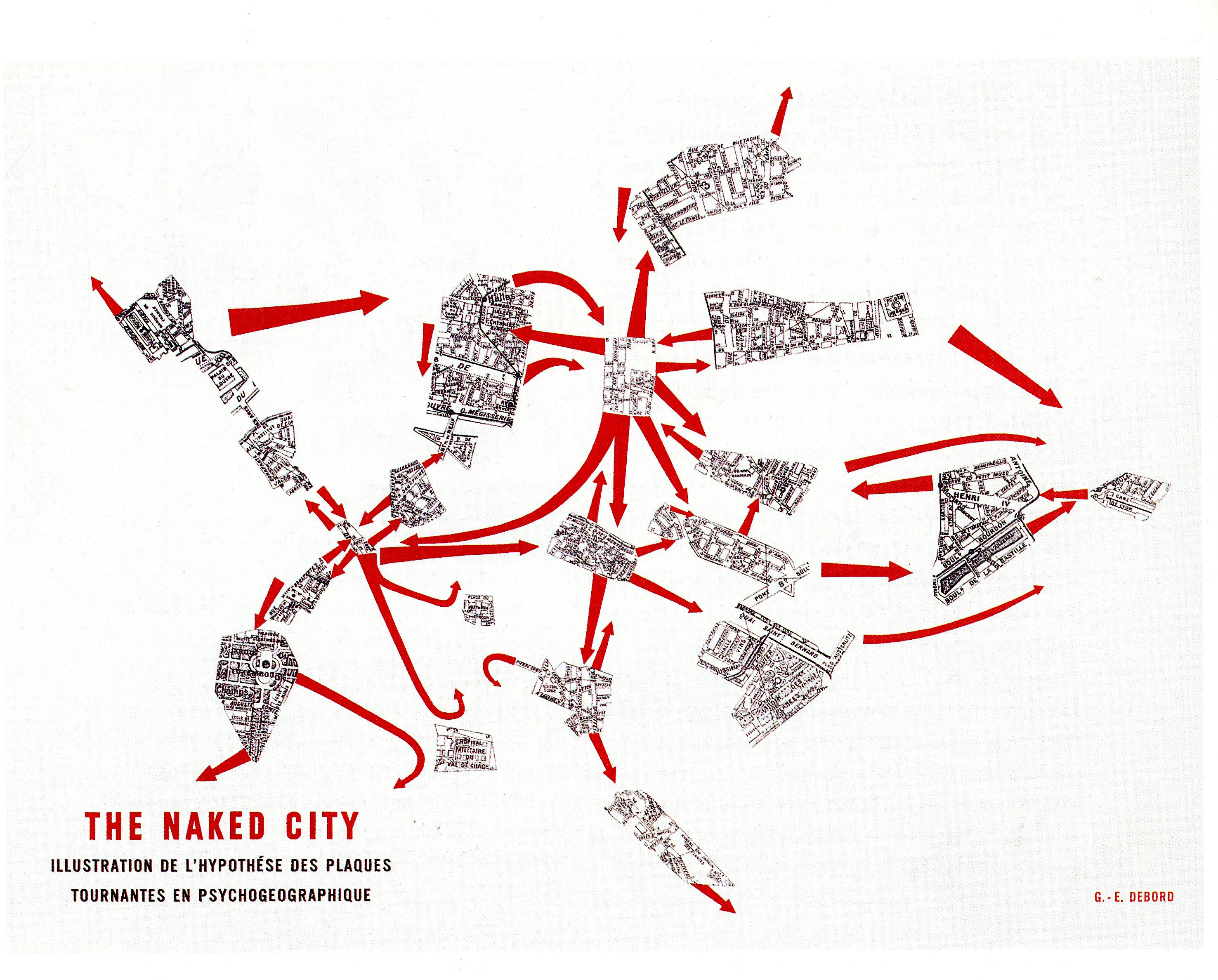

This post is an excerpt from Allan Haverholm’s article in the Uncomics print anthology. Main image: Naked City (1958), by Guy Debord.

I. The trouble with comics

Although comics are a fairly varied and diverse order of visual entertainment, the term itself has become entirely associated with the entertainment complex in which comics has developed since the late 19th century: In too many ways comics have evolved as a poor man’s blockbuster movies, under commercial direction from publishers to produce more of the same, but more hyperbolic with every iteration.

As a result, the audience (or “fan culture”) is unable to perceive anything outside those narrowly refined products as comics. A rather unhelpful non-definition of “I can’t tell you what comics are, but I know one when I see it”. “Comics” as a descriptor becomes instead a prescriptor that precludes work outside of commercial visual styles, or movements away from narratives that accommodate the dopamine rush of recognition.

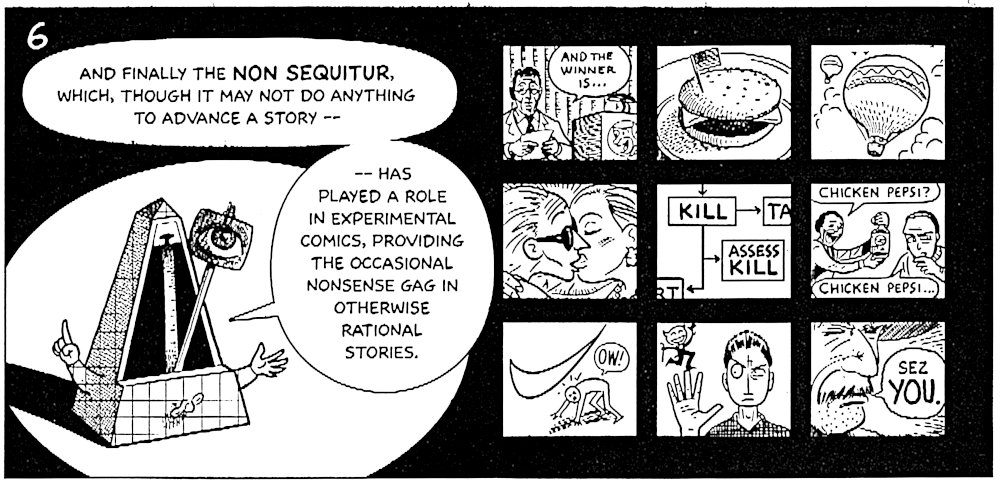

Like readers, comics scholars tend to define comics only as their surface qualities prescribe — “comics as they verifiably exist” — and wash their hand of the possible applications of comics’ formal traits. Conventional thinking sits at the core tenets of perhaps the best known modern popularizer of comics theory, Scott McCloud. His concept of “closure” (that is, montage) claims to exhaustively list the mechanics of transitions between comics panels, yet examples that fall outside of his purview of linear narrative are delegated to a “Non sequitur” category, so demonstrably silly in his perspective that he needs draw himself as a Dada-esque, cyclopean metronome to fully express it.

Excerpt from Scott McCloud, Making Comics (2006), page 17

As a practising creative working with the art form, however, I find it difficult not to poke at that missed potential. McCloud’s “Non sequitur” discard pile is rather the comfort zone of a growing number of like-minded experimental comics artists, only a few of which are included in this anthology. Even from a theoretical point of view considering comics in a wider cultural perspective, particularly relating to modern visual art, requires not only that we filter out the socio-cultural aspects of industry, genre and fandoms — and to that point a new terminology is very helpful to distinguish those from the art form’s latent formalities. I give you “uncomics”.

II. The field of uncomics

In summary, comics as a form of expression has developed in a bubble, separate from contemporary art, which still keeps them from accessing a wider spectrum of expressive potential. Yet on the periphery of that cultural cul-de-sac, well outside the mainstream that has corralled it off from the art world, can we find artists that bridge the gap. It is only there that comics can be considered to evolve and innovate.

With uncomics, then, we look for comics that seem to fall outside the common or popular perception of the form — or rather, its content; comics that don’t conform to straight narrative or drawing styles; that avoid if not exclude the use of text — and its tiered reading schema. Most crucially, to burst the bubble isolating comics from modern art, we need to focus on works drawing influence from, or extant in fine art movements and phenomena.

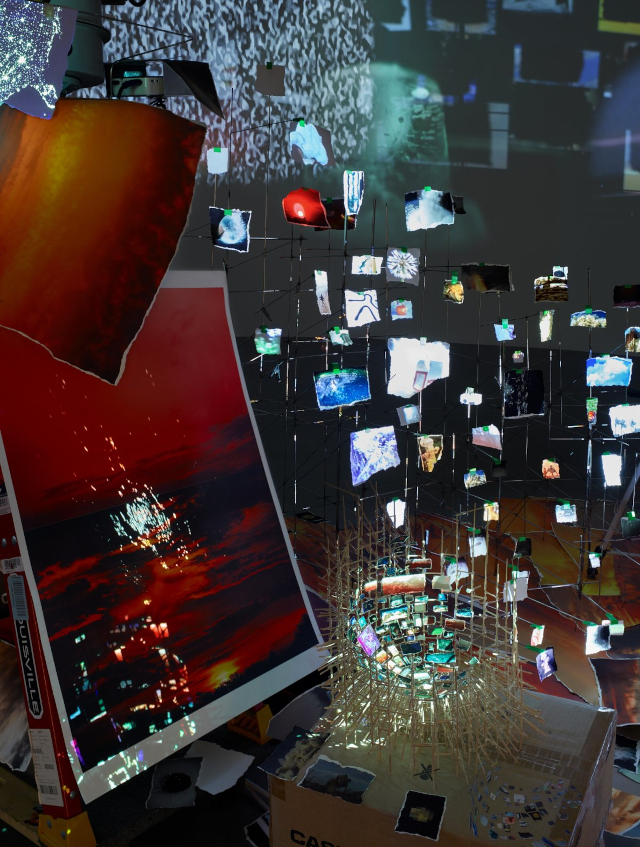

One significant example of such works in a comics context would be the Abstract Comics Anthology, edited by Andrei Molotiu and published by Fantagraphics Books in 2009. Tangential examples from fine arts could be Sol LeWitt’s conceptual artworks exhaustively presenting all combinations of, say, curve and diagonal line segments; Joseph Cornell’s curiosity cabinets; or Sarah Sze’s intricately composite installation art.

Sarah Sze, installation view of Flash Point (Timekeeper) (2018). Photo credit: Sarah Sze Studio

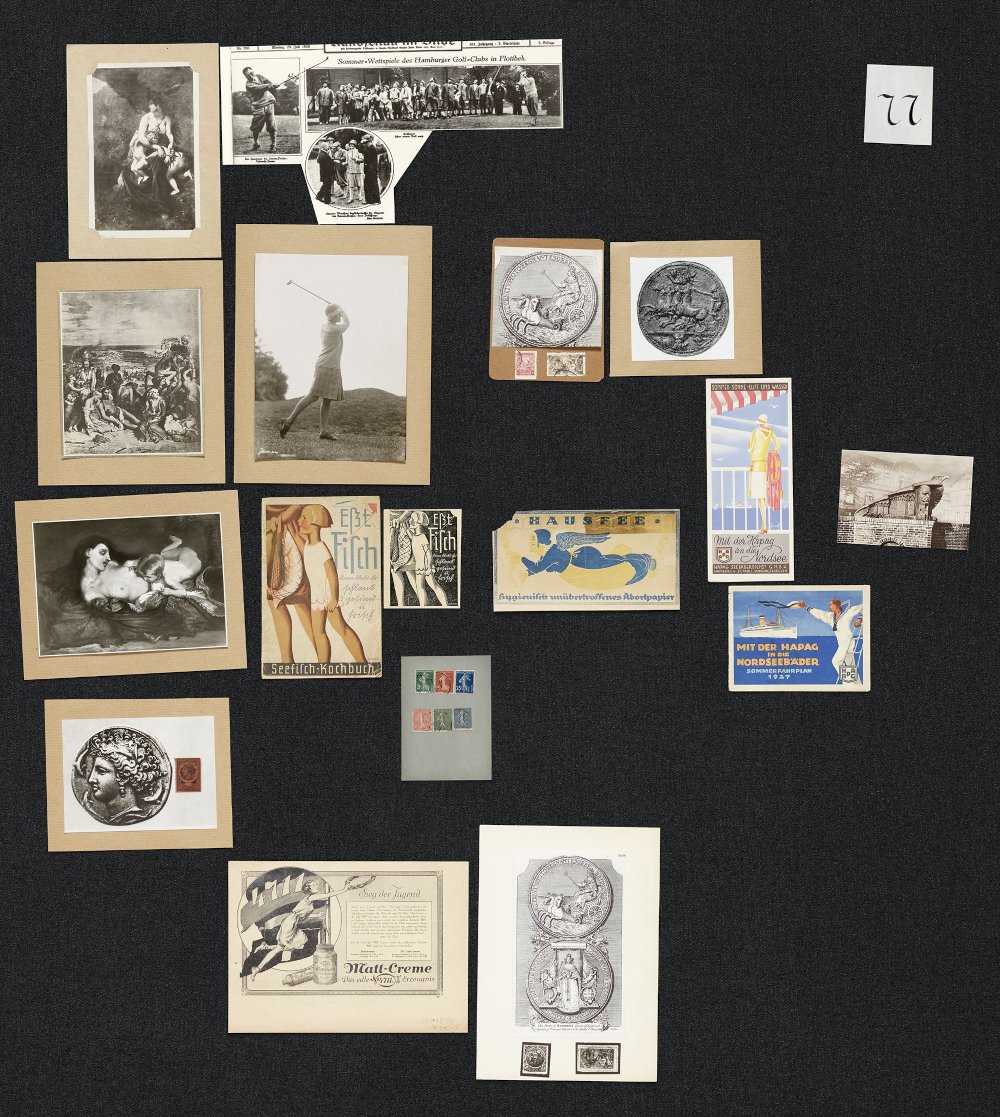

Similarly, formal comics-like traits can be found in the fragmentation of a subject in Cubism; the juxtaposition of disparate image elements in collage; Modernist usage of grid structures in painting as well as sculpture; the seriality of artworks exploring a subject through repetition; the codex manipulations of artist’s books; the ordering of massive visual archives; and the fundamental gallery practice of curation. Any and all of those corollaries are mutual in the sense that they serve to further inform our understanding of uncomics, and to merge pertaining (practical as well as theoretical) frameworks into the growing apparatus with which we analyse the field.

Aby Warburg, from Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (1925-29). Photo credit: Ivory Press

If I seem wary to define uncomics in too much detail, it is to allow for future inclusion. Unlike traditional preconceptions of comics, we deal here with a largely unexplored field that must encourage continued enquiry and speculation. Uncomics are only clearly defined by the socio-cultural limits delineating quote-unquote, capital-C Comics, and potentially encompasses instances of montage, juxtaposition and/or ambiguous networks of relations — in any other medium or cultural context.

To read more, read the Uncomics anthology, out now from CBK Comics!

To comment, please send an email to submissions@uncomics.org.

Any comments may be subject to publication on this site only. Your contact information will not be shared with third parties.