With his pencil as his witness — Warren Craghead (transcript)

This is an edited transcript of a conversation between Warren Craghead and Allan Haverholm on 2018-01-17. Listen to the talk in episode 3 of the Uncomics podcast. This talk was the basis for a feature interview printed in Bild & Bubbla #214.

Background

Warren Craghead WC: I grew up in a family of artists and creative people. My dad would draw cartoons with my brother and me all the time, my mom would do crafts and make stuff; both of my grandmothers were painters, I remember my one grandmother’s basement smelled like turpentine and linseed oil. Even now when I smell it that’s what I’m thinking of. So it was normal to make stuff, growing up. My brother ended up being a film maker and I ended up drawing all the time.

Through high school, like most American kids I grew up reading a lot of American superhero comics and my first attempts at comics were emulating those and making up my own superheroes. Then I graduated, like I think a lot of people my age did in the mid- to late ‘80s, on to things like Love & Rockets and early Dan Clowes work, and seeing that comics don’t have to be just genre work – nothing wrong with genre work but it can be about, you know, my life, Love and Rockets especially was influential that way. I remember I did some comic strips for my university newspaper that were complete ripoffs of Jaime Hernandez’s work [laughs].

So I graduated high school and went to university, and I didn’t know what department to go into because I wanted to do comics and in the late ‘80s, it was like comics were from the Moon, nobody was teaching it – except maybe in New York or some bigger schools I didn’t know of. I remember the study counsellor was like, “Well, you can go into commercial art,” which was more like illustration, “or you could go into Fine Arts,” and they sent me in that direction and, like in the Robert Frost poem, “that’s made all the difference”, that path.

By going into the painting and print making department, I became comfortable and enamoured with things like confusion, and mystery, and not nailing things down which is still there in a lot of my work – the poetry of things, I got that from painting and the Fine Arts world. I went through painting and print making and I drew a lot of comics, but I didn’t publish anything though I was towing over towards it. One professor in my undergrad would have certain characters and things through whole series of his paintings, and I started doing that and I started drawing little things, stealing from comics. It was almost like I was really wanting to do it but I wasn’t giving myself permission to.

Then I spent a summer at an art program in Maine, and I went to an MFA program, three years of graduate school at the University of Texas in Austin, and it was there I started making comics. I can remember the moment, being at at poetry reading – when I realized, “Oh! I can put together comics just like he’s putting together a poem”, where these lines don’t have to make narrative sense the way they do in a “cinematic comic”, they can hold together like a poem does, thematically or aesthetically, and tell a story the way I did in my paintings or the prints that I was doing. I went back to my studio that night and cutting things up, drawing and trying to put them together – it was really a Eureka moment in my head. I mean, it’s so stupid now but it was great to find that.

While I was at the University of Texas I started drawing comics seriously, like Speedy that I got the 1996 Xeric Grant for. My comics work still looked very cartoony but it was put together in a really strange way. My painting just fell away in favour of drawing and putting things together in order into, I guess you could say, “comics”. That sort of has been my default way of working since then.

My wife’s family is also super artistic, too. She’s the only woman that I’ve dated whose dad was excited that I was an artist. All the others were… they were not happy!

AH: “How are you going to provide for her?”

WC: Exactly. She was a modern dancer, both of her parents were artists, her whole family is full of artists, so it’s been good. And our kids are both doing a lot of theatre, they had a musical theatre rehearsal for a play tonight; they’re in Fun Home, based on Alison Bechdel’s comics! Crazy, right? My oldest daughter who is 12 plays the younger version of Alison; she did it in a show last fall and now she’s doing it again. And my other daughter is nine, she’s playing the younger brother of Alison. You can’t escape comics and drawing! [laughs] I’m drawing you now.

Allan Haverholm, drawn by Warren Craghead during this talk.

That’s where the art stuff started, I’ve just been drawing since I was a kid and I think it took me a long time to realize I could do it seriously, and then even longer for all the streams of things I was doing to converge into the work that I started around the turn of the century putting words and images together in a non-cinematic way, and finding value in “art people’s work”. I still hold a lot of those Fine Arts values, you know, I look to people like the American Cubist painter Stuart Davis, Pablo Picasso or Philip Guston as people that I steal from all the time, Giotto is someone that I steal from all the time.

That sense of ambiguity and confusion, that it’s okay for things to be multivalent and not nailed down, and also not necessarily telling a straight story. That freaks people out. I try to straddle between the Fine Arts and comics. It’s funny to see over the last 25 years how, at least in the United States, the distance has collapsed between the two. People like Renee French or Aidan Koch who are fully at home in both worlds, and obviously Chris Ware – he’s kind of operating in the stratosphere of things, being in the Whitney biennial and all that – but I think much more of the Fine Arts world understands this stuff and can operate with it now – it’s good.

When I first struggled making this kind of crazy work, I had a lot of pushback, “Go back to art school!” because my pedigree wasn’t from the undergrounds, Crumb and Spiegelman and that kind of stuff. Now I see more and more young artists who are like, “I don’t care about Crumb – I don’t hate it or not like it, it’s just not where I get my inspiration,” it has changed a lot and the world is catching up with us. Although, we’re still seen as making weird stuff, so –

In the States at least, you’ve really had to define yourself against Superman and Batman, like, “I’m not about that!” And now you see Dash Shaw and the Strange Tales stuff that they do, they’ll get really out there alternative people to do superhero stuff. That’s what you get when you get old, you get to look back how things have changed, and be the wise elder, as opposed to – I don’t know about wise, but you get to be the elder, or old! [laughs] And hopefully you’ll still be making work that’s relevant and strong.

Seed toss

When I started Seed Toss, I had moved to Albany, New York, which is a smaller city where my wife was at school and I only had her family there, and I was feeling cut off in a lot of ways. So I started making work to deliberately put it out into the world, to sort of use the world as a publishing platform. I would draw on postcards and just mail them to people. I still do that, for example I have a relative that’s really sick, I send him postcards all the time, just random drawings. Then I started drawing on Post-It notes and leaving those on various places – I still do that all the time as well, and documenting it and sharing it.

- A drawing left in public space, 2021

- A drawing left in public space, 2021

- A drawing left in public space, 2021

- Mail art, 2015

To me it’s about enchanting the world a little bit. I’ve done some street art, but I don’t want to do anything destructive. Any time I’ve drawn on a wall it’s been in pencil so it’s easy for someone to clean up. There are buildings I wouldn’t mind being destructive on, Trump Tower or something like that [laughs] but when I draw on these Post-It notes people can take them or leave them; throw them away, whatever. Once they’re out of my hands they’re out in the world, and yet I find people like them. People have discovered them or found them. I had a show up just outside Washington, DC where I had a whole wall of Post-It notes that you could take down and take with you out into the world and send me a photo back. And I posted those photos as well to show how the drawings scattered all over the world. Somebody took some and travelled to Europe and was leaving them at some places in Europe.

- Post-it art, exhibition view

- Post-it art, exhibition view

- Participatory mail art, exhibition view

- Participatory mail art, exhibition view

I had postcards at the same show where you could write an address to someone and put it in a mailbox I had, and I’d mail them out to people. I draw so much, I just wanted to find a way to give it away, I guess. Send these things out into the world and let people find them. So I still do it sometimes, I’ll go to someone’s house and I’ll leave a Post-It note in the bathroom, or I’ll do it at a restaurant. What’s funny is, when we go to a restaurant, I see that my one daughter will be doing drawings and then she’ll give them to the cook. It’s rubbing off on them, this idea that you can just send this work out into the world and not necessarily expect to get anything back.

Even in my pocket right now I have this home-made sketchbook that I carry around; I usually have a bunch of Post-It notes in the back so wherever I am I can leave one. I guess I do it more now by publishing stuff online for free, on all the Tumblrs and microsites and things that I post work on now. In fact, right before this interview I put up a Trump on Instagram. I think it becomes tiring to do all of these social media places [A Facebook message pings, right on cue] but each of them has different audiences. Some of the projects I do, I want more people to see it, so that the work becomes part of the conversation. Mostly so with my political or socially engaged work, but even with my poetry work that’s about quieter, less bombastic moments. I think it’s good to have more art out in the world!

When I’m getting a book ready, instead of throwing test prints and proofs away I’ll go out and staple them up on telephone posts or just leave them in kiosks, stuff one into each newspaper in the newspaper box. With no context, though, the people in my neighbourhood have no idea. I think Seed Toss is a fun, anti-Capitalist thing to do because I’m not selling the work at all, I’m just letting it go on the world. So in that way it’s really freeing to do that, definitely. It’s not like the rest of my work has a great market and I make a ton of money but there is deliberately no way to monetize this. And it’s fun!

There’s a punk rock quality of fun trouble to it. Like being a mischievous imp or a sprite, a crafty little leprechaun leaving those things around. You don’t want to be child-ish, but it’s good to be child-like, and Seed Toss is definitely a childlike thing to do! Another thing about being childlike is to be constantly curious, when I’m drawing stuff I’m always discovering, figuring out how to draw things, trying to draw them in different ways, being excited when I do figure it out and later on dropping that and trying something else. That openness I think is something I really enjoy about making work.

Fauves

- *Fauves* 90

- *Fauves* 92

- *Fauves* 96

- *Fauves* 100

AH: I see that a lot in your work, even when you’re drawing the Armenian genocide project, but where it comes through the most is probably in the *Fauves* series.

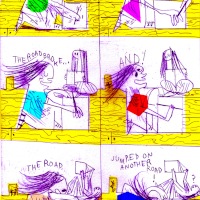

WC: As my daughters grew up they would say and do crazy things like kids do, and once I started writing them down in my sketchbook I realized I needed to draw these. I read about a photographer who made a series of pictures of his daughters which he talked about as “trying to tell the story of teenage girls”, and I realized that it was an act of love for them. He’s paying attention to them and trying to really see them. And since I don’t take photographs, I started drawing them. So I made those drawings in a few comics of my kids doing things, and I was really pulling from this biomorphic Cubist drawing style, trying to manipulate and pull things apart. It’s been really fun because I feel I can pay attention to the kids and be a part of what they’re going through or understanding them, at the same time as I’m learning how to tell comics this way, and use keyed-up colour.

Later, Frank Santoro invited me to do some work for his Comics Workbook, and I made Fauves in a similar style of drawing. They’re called Fauves because it’s French for “wild beasts” and the fauve painters would paint in these bright colours, and I thought “Well, they are beasts, these children – who are crazy.” And also, the colours fit, so it was perfect! I started drawing them a lot, and now the kids call themselves fauves sometimes. I had a show at an art space here in Charlottesville where I live, and part of it was a big wall of the Fauves artwork, and the kids were stood in front of them and had their friends take their photographs. Of course, the comics are of them talking about pooping or whatever, but they were so proud of themselves! [laughs]

A variety of expression

It was on the one hand me wanting to pay attention to my children but also wanting to make work that I still thought was aesthetically engaging. I wanted to investigate how to tell a story in this way that is sort of “push and pull” figures. If we look through Fauves you can see me stealing from different things and trying them out, sometimes very aggressively abstract, sometimes I fall into a certain style with them for several pieces and then try to break out of that. I’d draw with ink sometimes and then with pencil – always trying to make something new.

When I look at some of the things that I draw, some of them are very cartoony and some are not. I think it just comes from drawing all the time, so you end up drawing things all over the place. It’s funny because I always thought of myself as this very serious Fine Arts, poetry comics guy, and never as a cartoonist. I didn’t like that term because it meant certain things to me, and I resisted being a regular cartoonist for a long time but I think some of the work I’m doing now is definitely cartoony. The way I was trained and the way I started making work was to always investigate, always try to draw things in different ways, but sometimes it does get a little crazy to handle all these ways of making different things. [laughs]

I think I have a restlessness, but there is an understanding as well of how different ways of drawing can work better for different projects. So if I drew the Fauves the way I draw Trump Trump it wouldn’t work as well. The Fauves work can be crazy and bouncy and cartoony; Medz Yeghern which is about the Armenian genocide needs to be more gritty and more to the bone. You can especially see an aggression develop in the daily Trump things as they go on, and in the Ladyh8rs and USAh8rs as well. As I go on and on I get angrier, but also better at showing that with a pencil, you know? [laughs]

- Ladyh8r — Montana District Judge G. Todd Baugh: Suspended all but 31 days of a 47 years old man’s 15-year sentence for raping a 14-year old.

- Ladyh8r — Jay Townsend, a campaign spokesman for Republican Rep. Nan Hayworth: "Let’s hurl some acid at those female democratic Senators".

- USAh8r —Twinkle Andress Cavanaugh, president of Alabama’s Public Service Commission, called for God’s intervention in regulations on coal.

- USAh8r — Sen. Ted Cruz filed to force the federal government to sell off a significant portion of the country’s most prized lands in the West.

I learn some tricks to drawing caricatures of people that I’m sure most people pick up much quicker than me, but my artistic secret is, if you do something every day you’ll get okay at it eventually. [laughs] Let’s put it this way: The Fauves work I feel are loving embraces of my kids; some, like Medz Yeghern is really sad and me trying to make sure it’s not forgotten. The Trump work is me out there in the streets, attacking him as best I can, [laughs] alongside Antifa or whoever else is fighting the Nazis!

Medz Yeghern

AH: I want to ask you about those repeated motifs you have throughout Medz Yeghern which I think help emphasize that sadness you’re talking about.

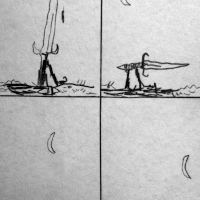

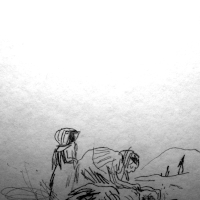

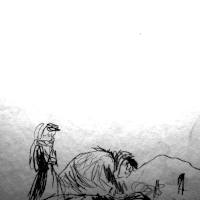

WC: There is that one image that I’ve been drawing over and over for almost a year now, of a woman bending over her dead child, right outside Aleppo which to the Armenians escaping the genocide was a degree of safety – so many thousand died right on the edge of safety. That one image kept coming up as I was looking for images to draw, but I always held back from it because I didn’t feel I could do that image justice. A hundred years ago they weren’t taking as many photographs as we do today, so this was a very powerful one. On April 24th Genocide Remembrance Day of 2017, I started drawing that one image once a day, and I’m drawing that for the entire year, which I have never done before.

I think that with that repetition I’m finding new things in the drawing, I can draw it from memory. I’ll just storage certain parts. If you look over this year’s drawings you can see certain parts of the photograph that I really like to draw and start pulling it apart, pulling it back together. The girl on the ground, I really love drawing her hand. Maybe some people can just do the same thing over and over again, but I think your mind is just naturally going to start changing things around and doing things in different ways. There are times that the persons get small and I’ll draw all these monsters around them with knives or whatever. And there are times when it’s very simple and serene.

- The Armenians' escape through the desert to Aleppo is a recurring motif throughout Craghead's *Medz Yeghern*

- Knives, half moons, smoke, pebbles --

- -- and more concrete symbols of the Ottoman persecution of the Armenians appear throughout.

- Another recurring motif: Images of those perished in the Armenian genocide, reduced to ashes.

In contrast to this work, as well as some of the work I’ve drawn about Syria, the Rohingya in Bangladesh, the situation in Yemen – here I am, pretty much as privileged as you can get, so far away in the United States and so safe, I see these things and I want to draw them. I want to at least make sure that I’m really looking and seeing them, and hopefully making other people see them as well. I know I’m just a drop in the bucket, but I want to do something.

AH: You talk about Medz Yeghern and your other historical projects as witnessing and remembering by looking, but what about the recurring symbols you use, like the sword or dagger – ?

WC: I’m glad somebody was really looking. [laughs] I appreciate it, because I think that project doesn’t get as much attention as other works. There is a dagger or a knife that is frequently threatening or actually killing people. There is a crescent moon which, to me, is threatening – obviously, it’s the Ottoman government that was ordering the killing. Sometimes, there are sunrises and I’ve tried to also draw the beauty of the Syrian desert where the Armenians were driven out. There are also several drawings where you see is a hand holding a pebble.

Drawing the same image since last April is a little different, but for two years before that, the practice of making a drawing every day meant I had to constantly come up with different things. For a while I was only drawing fire and smoke; sometimes I drew specifically from photographs, and other times I just made up things in my head, like a kid. And I tried not to be too horribly sad, although the subject is that, and I constantly tried to figure out how to make these things work.

- Woman with dead child outside Aleppo, one in a year long series of drawings

- Woman with dead child outside Aleppo

- Woman with dead child outside Aleppo

- Woman with dead child outside Aleppo

I came to the project because my wife’s stepmother’s family, who we are very close with, is Armenian, they’re a very artistic and loud family. I was already doing the daily WWI project La Grande Guerre, and the genocide was started during that but I didn’t just want to do one day of the Armenian genocide. When I was researching it, I realized that although there had been pogroms before 24th April, that was the date the genocide started: That’s my birthday. And I thought the universe was telling me something…! I don’t usually go for that stuff but I thought I had to do this, so I started just drawing it every day.

I have a problem, I know this about myself: I have a hard time distinguishing between what I can do and what I should do. What I mean by that is, if I think up a project – like drawing World War I every day, what happened every day on the date – I’ll do it, not thinking that that’s a crazy project to do. Or, “Hey, I’ll draw Donald Trump every day,” I’ll do it. La Grande Guerre I started in 2014 and I’m still drawing it every day. You can tell, this thing went on so long, and it’s the same with the genocide. I’m actually not sure how I’m going to end the genocide project, because it sort of peters off as the Ottoman empire crumbles, the Turkish state starts and the remains of the empire is carved up by the allied powers.

Trump Trump

Trump Trump was an offshoot of the Ladyh8rs and the USAh8rs projects. I started Ladyh8rs because in Virginia where I live, the state legislature had a bill that was, without going into details, a really misogynist way of trying to restrict women’s rights to abortion, and I got really angry because here in the United States, state governments can get away with a lot because know one knows who they are, everybody pays attention to the president and all that. I started drawing them and saying, “This is the person who was trying to take away your rights, this is the person who was trying to defund your school,” or “This is the person who was trying to do this racist thing.”

- cover of the first *Trump Trump* collection

- cover of the second *Trump Trump* collection

The Trump Trump project I started on the night that he was nominated for president; it was surreal, it was crazy here. I thought, “Oh, I’ll be drawing until November. This is no big deal, he’s going to lose!” Well, of course he didn’t. So those early ones were just me drawing portraits of him that are… unflattering, but they’re not too crazy. The first time I drew him naked I was just laughing and thinking how crazy I was. Looking back from what I’m doing now, [laughs] the newer stuff like what you have on the cover is super crazy! I can draw people in a horrible way. I can’t draw people nicely but I can draw them as horrible monsters now. As it went on I started drawing his minions, I started drawing all the things that he’s trying to do to us and, honestly, to everybody in the world. It’s really weird here right now, man. It is really weird, especially here in Charlottesville where the Nazis marched and all that.

More and more I try to highlight the super right-wing policies that they’re trying to push through. The anti-environmental things, the racist things, and again just try to draw them in this cartoony way. I think a lot of the poetry comics work – and I’m using that as an umbrella for a lot of that stuff – they are kind of opaque in the sense that what it’s about is mixed in and mysterious and not on the surface, whereas this work is all on the surface. [laughs] It’s all out there!

And there are all these characters, there’s a little piece of pizza that runs around, to me it symbolizes all the fake right-wing memes and stories that go around [in reference to PizzaGate]. There are all sorts of things, sometimes there’s a hand that comes down from heaven, to me that’s the Kochs and the Mercers, the wealthy right-wing donors who just want their tax cuts. I try to avoid the political cartooning tricks of “the hand holding a bag with a dollar sign on it means Money” –

AH: You do have the Ku Klux Klan-silhouette popping up now and then.

WC: I go back and forth, sometimes I’ll steal that stuff and sometimes I won’t. Those Klansmen are stolen completely from Philip Guston’s late paintings, and I steal from Saul Steinberg a lot. I’m giving you all my secrets! [laughs] I look at a lot of things and I steal from a lot of things. I’ll steal from Giotto or Käthe Kollwitz, from Otto Dix or George Grosz; all of those inter-war, German Expressionists and graphics people. I don’t know if I’d steal from Jack Kirby, because I love him too much and [laughs] I’m kind of scared of him.

To me there’s a way of stealing, my friend Austin Kleon wrote a book called *Steal like an Artist*, and you can steal like an artist if it’s being transformed, if it’s becoming something new. And again, in doing something every day I’m constantly looking for new ways to make something, because it gets boring or I look lame. I want to continue to make cool stuff. Another good thing is that you can look back at old drawings and realize, “Oh yeah, that was awesome! Let me go back and try that again!” And you end up with this reservoir of ways of working, and that’s true of my poetry comics stuff as much as it is of my more cartoony stuff. I’ll remember that, “Oh yeah, I was doing all those drawings of these guys going surfing,” and I’ll want to go draw some more of those. Put them together into a story.

Participation

I mean, you find your own history, you make your own history. Then you can go back and look; as we get older we’re slower, and I feel kind of dumber than I was, but I’m more tricky and cunning than I was. [laughs] Part of being an artist is making stuff, and part of that is participating, reading, talking, being a part of it. It’s not just me by myself drawing. Part of being an artist has to be participatory, and I see that here in the States – there’s such a rich festival culture that people go to all the time. They’re like big flea markets, people standing behind tables… [laughs] and yet people go because, I think, they want to see people.

They want to talk to people who like what they like. We’re watching Project Runway right now, in the episode we watched tonight this young designer was voted off, he is a young man but he’s very wise, and one of the things he said was, “What I’ve valued most is being around people who value the same things I do.” People like going to MoCCA or SPX because you’re around people who value the same things as you. I’ve come to the Small Press Expo, which is a big comics festival outside Washington DC, since the late ‘90s when I was the young one, and now I go and it’s amazing to see – it’s not just that the generations have turned over, they have turned over a couple of times and you have all these young ones running around making great stuff! Some of which I don’t like because it’s not for me, which is awesome! [laughs]

Some of it I’m totally confused about, but then again, people like Andrew White, Madeleine Witt or Alyssa Berg are making some amazing, just avant garde work that is thoughtful and experimental. Andrew, to me, is not afraid to follow where things go. I’ll try not to gush about everybody else. The internet has helped a lot, too – there is a lot of people doing weird work. It is really helpful to me to know that there are people I respect who are making great work and that I can actually be in contact with, as opposed to being alone by myself in the middle of Virginia, the middle of nowhere. [laughs] Just doing my thing.

Actually, when I look at some of those people, Simon Moreton is making the best work of his career, Minor League is frigging amazing; and Oliver East surprises me all the time with the crazy stuff he puts online! It’s good, I get jealous. I got to keep up with these guys! And that’s the way something like this Trump project can be a burden. I’m going to do this because I’m really stubborn, I’m going to do it, but there are times when I wistfully think, “I want to do some of that kind of work!” I can do a little bit of it, I just had a piece in Ink Brick, it’s just hard to get that work together – like, I drew a Trump at lunch so I can do this interview tonight.

The political landscape of 2018

AH: Let’s hope he doesn’t say anything totally outrageous during the evening so you’ll have to backpedal and catch up.

WC: No, right! Well, that’s the thing, I can’t keep up with him sometimes. I’m scared to check his Twitter feed. If he somehow tweeted about this book, my work or the project, I would be so happy. I should send a copy to the White House, but with a fake jacket on it to make it look nice, and then of course one look at it – We’ll see. I went to New York after the inauguration, in March of ‘17. We were up there for a relative’s funeral, and I realized the hotel we were staying was like, five blocks from Trump Tower. My family was asleep at the hotel, so I thought I’d go out for a walk, I just walked around, and there was Trump Tower… I’ve left some Trump stickers around, and I realized that I’m perfect for doing this – there are a lot of security and police officers there, obviously.

But here I was, this middle-aged, white guy who looked like a tourist from Virginia, so I just looked like a country bumpkin. And I was leaving tons of stickers all over, right next to a police SWAT team. I’m standing there, leaning against the wall and just putting a sticker up, acting like I’m on my phone – they didn’t look at me twice. If I’d had a mohawk or nose ring, or, god forbid, dark skin they would have been all over me, but I looked totally harmless. [laughs] But yeah, that was after the horror started.

I don’t know what Swedish politics is like, but I’m sure it’s not this crazy. Maybe it is, I don’t know.

AH: I’m trying to imagine how you must feel over there, knowing it’s more or less a 50/50 split between Trump and the Democrats.

WC: There is a lot of soft support for Trump, people trying to look aside from some of what he’s doing, and in a way that was one of the impetuses for the Trump project when I started it. On the one hand I wanted to give strength to people who hated Trump and were fighting Trump; on the other hand, I wanted people who were softly supporting him to not escape the racist and horrible things he was saying. “You can’t vote for this!”

About the Trump book, I don’t know where it’s for sale over there at all. [laughs] I’m less interested in money than I am in spreading it, getting people to see it. And I especially want people in other countries to see them because I want them to see that most of us hate this guy. [laughs] It’s not us! I’m so sorry! I was just apologizing to my friends from South America, “I’m so sorry, man!” But I get to draw this stuff, it just has real life consequences for people. I try to remember that.

About ten miles from where I live, there’s a winery that is owned by Donald Trump. They have an event space, like a hotel, and I was trying book that to have the launch party for the Trump Trump book there. And they got back to me saying, “Oh, this will be great,” but then I think they must have googled my name because they just stopped emailing me – at all – once they realized what the book was. [laughs] That would have been the best troll move if I’d had this launch party there. It had been so good if they’d kicked me out, that would’ve been great!

AH: Other than that, what have the reactions been to the book?

WC: Most of it has been really supportive, I have had a couple critiques from the right and the left. The actual substantive critique from the right, other than telling me I’m an idiot, was that “You’re just as bad as him because you’re drawing him in horrible ways,” but there’s a long tradition of caricature as a place for political battle. From the left people have said that they’re uncomfortable with me profiting off of Trump’s statements, even if it’s ironical. I thought about that a lot but I’m not really profiting, I’m more amplifying what he’s saying but in a context of grotesquery. But I understand where they’re coming from.

There’s an art and comics store here in Charlottesville that’s really great, Telegraph Comics; they had a signing for me with the book, and they told me that a guy and his kid had come in and he goes, “Ooh, there’s a Trump book!” He picks it up and starts looking at it, and I guess he was a Trump supporter because he went “Ohhh…!” and then he puts it down and he backs away. [laughs]

People have news fatigue here, you’re just worn down from paying attention to so much stuff, which is why I’m trying to draw more and more of the actual policies that are happening, rather than just the latest horrible thing that he said; opening up all of our coastal lands to oil drilling. It is more important than him saying a bad word. The comments he made about African countries and other countries is indicative of the sort of racism that he helps happen. I don’t think the Nazis would have marched here in Charlottesville without him saying these things.

The Charlottesville rally

In August, my family and I were out of town, we left on vacation the day that it happened. My wife says it’s a good thing because I would have been down town, which I would. There was a Ku Klux Klan rally here earlier this summer, I was right at the front drawing them the whole time.. So, we watched it from afar for the first week, but when we came back, it was pretty crazy. I work at the university here, and that’s where the night before they’d done their march with the torches. There were a lot of people very shook up and weirded out by all this, very angry both at some of our leadership in the city, but also, of course, at these horrible people that did this.

Things are in such a flux here, there is a lot of people that are really activated in a way, you could say “radicalized”, but it’s not necessarily that they are super left. It feels like a lot of people have woken up from complacency, and they realize that there are some real problems with the way our government works. I think that Trump is a symptom and not necessarily the cause of that. Getting rid of him is important for so many reasons, but it’s not going to solve other problems, the attitudes are going to remain. There are some real battles to come.

The left here is so weak, it’s probably a lot like the right in some European countries. Let’s put it this way: Socialized medicine, which is the norm in most other industrialized countries, was a far left-wing position a few years ago. We were crazy communists to want that. Now, I think it’s almost the default position of the Democratic party. That sort of thing is good.

AH: It wasn’t until Bernie Sanders called himself a social democrat during his campaign that it occurred to me what different connotations that has in the States.

WC: Oh, it’s a bad word here, yeah. The right has done a very good job of controlling the language and controlling the way that we think about these things. There is a lot of weird ideas about things here as well. But the actual policies, things like, that the social democrats, in Sweden might believe in – people believe in those. There is a deep reservoir of people her that believe we are all in this together. That’s really what it is. Are we all in this for ourselves or are we all in this together? Which one is it?

I think that people do feel we are in it together. There’s such a deep history of racism that has been used as a lever by the right here for so long that I think it’s hard to get past that. I just know that there is a lot of people I know that are a lot more active and energetic now than they ever were, and that’s good. The Nazis were trying to have another march in Charlottesville on the anniversary of the first one in August, and they were denied a permit.

I haven’t drawn much about what happened that time, and I think it’s weird that I haven’t, but I think it’s because I don’t know what to draw. Maybe on the anniversary of it I’ll try. All the photographs of where the car drove in and killed that woman, that’s a block from where I used to work, that’s where we go all the time. Actually, my kids and I were there a couple of nights ago, it’s like, right here. It’s a small city. I don’t want to over-dramatize it but it was pretty terrifying. It redoubled my efforts to make sure to draw things that matter, that are important.

That doesn’t necessarily mean political, some of the aesthetic and quiet poetry comics work is also really important, it’s important to have these experiences and to value the world in that way as well. It doesn’t always have to be overtly political and socially important, but I do think doing that work as well scratches an itch that I have to not be so separate from the world. I started doing a lot of that political work when the Arab Spring happened a few years ago, because I was watching the stuff in Tahrir Square in Egypt and I was amazed, it was incredible what had happened! Now, it hasn’t turned out so well but at the time it seemed incredible.

Daily practices

It’s funny too, because before that I never really drew people, ever, and all I draw is people now. [laughs] But Picasso used to talk about this, he would draw the person and when the person goes away, the painting is now the thing, the objects of the world. One of the things I value about Cubist painting a lot is that you’re not looking through a window at something, the painting is what it is. It’s very inspirational to me and I steal from it as much as I can, because it comes out into the world, it is a real thing in itself, as opposed to a window to look through. There’s nothing wrong with the windows – cinematic artwork, the cinematics of comics – there’s much of that work that I really value and love. But I also love this work that sits on that surface and, you know, doesn’t necessarily always go in.

Some of Simon Moreton’s work just sits on that surface and you know it’s a mark, and yet it’s also signifying and drawing something. I think Alyssa Berg does that really well too, that tension between depiction and material, and in a weird way Renee French does too, maybe because I watch her videos where she’s drawing and you can see the graphite kind of build up? So it definitely feels like material and at the same time it’s an image. She’s another artist that I greatly admire. A few times I’ve met her and seen her draw, and she had some crazy contraption to cover her hand or whatever; the more you work on specific things, you come up with systems and ways of working.

I have a day job and I have a family, a house and dogs, so I have to come up with all kinds of tricks and schedule things, otherwise the work doesn’t get done. Maybe that’s another reason for the daily practices. I can’t just slack off and go watch TV, I’ve got to do this today! I’ve talked to students at the university about this, when you get out of art school, most likely no one is going to care about what you’re making at all. [laughs] So you have to find ways to make it and one way is to make it about things that you care about, and another is to make it as easy as possible for yourself. I carry these home-made sketchbooks around in the back pocket of my pants so I always can draw all the time.

Finding ways like Renee’s ways to draw, I know we all have our strange little methods. A lot of times I’ll be drawing my kitchen table at home. On the weekends my kids will be hanging around and they’ll draw with me while I’ll be drawing a Trump or something else that usually I’m alone and concentrated on. I have got to find ways to work with everything – also, because I want them to see that Dad can be a dad and also have a job, and he can also be an artist. You don’t have to let go of some of the art stuff because you went up being a graphic designer, or a doctor.

My kids do a lot of theatre with people who have regular jobs, and – my wife is a great example, she’s amazing. She’s a physician and a former modern dancer. She just did a musical theatre play here in town; she loved it, it was great and it was a great show, and I hope that we are showing them that you can continue to be creative and actively engaged in pushing things forward, making new things. While also having to have this regular life because I have to pay for my car and my house.

I find it really liberating that I don’t make money off of the work [laughs] because I can just do whatever I want. I certainly have a lot of respect and admiration for people who find ways to make it work, I know that it’s very hard. I’ve been lucky that I’ve been able to have day jobs, I’ve been able to pay for myself while also making things that I wanted to make, not having to worry about whether it sells or not. In fact, the Trump book is the one that I’ve been most anxious about, mostly because I want the publisher, Retrofit Comics to make their money back so they’ll do the next volume. It’s funny, I’m more worried about them than about me. [laughs]

I don’t know how most artists do it. I know some have regular jobs, others sort of cobble things together. People find a way, there is a lot of artists online that I follow on Twitter and Facebook, and I see how they cobble it together. It’s not an easy road. I feel lucky, making this kind of work, because it is supportable – again, tiny, home-made sketchbooks! I don’t have to have a big studio, I’m not welding things together, I do the absolute dumbest thing. I can go to the grocery store and buy a pencil, a piece of paper [laughs] and I can make a god damn comic out of that! [laughs]

That appeals to me, that it’s as independent as it can be. Making zines and xeroxes, that lo-fi publishing is really exciting to me, and I can tell that other people get excited! A friend of mine who’s an artist and teacher, his name is Ryan Trott, he has done all these very comics-y and graphic drawings and paintings, but lately he started making these books and I can tell – he has mini comics zine fever! He’s crazy, he’s making all these books now, and it’s great to see, it’s really wonderful because maybe he knew this from before, but people realize that they can make this one thing, and then they can amplify it out into the world.

On the other hand, here is a drawing my daughter did of the Butt-head Planet, with Fart Face City on it, so this is where we are sometimes in my house! [laughs] They draw a lot, and I save it all. We generate a lot of paper. Actually, there’s a big bunch of pens right here that they were drawing with earlier tonight. Like I said, I want to make it feel normal to make things. And they know, “Oh, you’re going to talk to that guy in Sweden!” It’s totally normal to them. I don’t mean “normal” in the sense of “mundane”. They were looking at [your book(https://www.hybriden.se/product/when-the-last-story-is-told-9789187825026/)] earlier and going, “Oh, this is cool,” it’s normal to them. They don’t know it’s crazy! [laughs] That’s good! They know that this is… art.

Drawing as an interface

I’ve had people back away from my stuff at festivals, this young lady came up to me once and said, “I’ve seen your Fauves on Comics Workbook,” and then she picked up How to be Everywhere, one of those books, and she was like, “Okay-y…!” and just walked away. [laughs] A long time ago I was at a comics festival in Lisbon, they had all the comics people at these tables for signing books – I’m nobody here, but I’m definitely nobody there! – and so I’m just chatting with people, Milo Manara is two seats down from me, so of course there’s a line out the door for him. And I keep seeing people look over at me and take pity, so they come over. And they go “Oh… Okay…” and they go back in line for Manara. [laughs]

It was great. I still do work of that poetic, personal nature – and then there are the projects that are very political, very social, that are also important to me. The book I did about the Syrian families who were gassed by Assad was a really hard book to draw, but it’s also really important to me to make myself really look at those pictures, because the media weren’t showing them, nobody was seeing them. This is what happened, these are the victims of what happens. I’ve done a bunch of drone drawings, of drone strikes that the US government made, real things that happen! And yes, some of the people killed in these strikes are bad, but a lot of them aren’t.

- *untitled* (2014) cover

- interior art

- interior art

- interior art

I feel lucky a lot of times that I have drawing, and making art in general, because it’s a way for me to interface with the world, to document the world, to react to it in a way that is hopefully positive. And mixing that content in with the aesthetic and formal things that are also really important, because I’m very focused on making a good drawing, [laughs] on making something really good. Anyway, having some art thing to make or some way of making art, I think is really valuable because it lets you have this kind of outlet, I know it sounds corny, but I feel lucky that I have this and that I don’t just yell at the TV all the time. [laughs] Or cry. Whatever.

AH: Talking about TV, what happened to your Project Runway project?

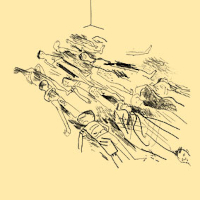

WC: Project Runway, I love that show because I feel like I’m watching artists at work. I never liked the cooking shows because I couldn’t smell or taste the food, and in making the fashion I feel that I can see what they’re doing. That’s a good example of me liking a show so I do some drawings based on it, but I haven’t drawn much from TV because I haven’t been able to watch much TV.

I do that a lot at plays, the production of Fun Home that my daughter did was about an hour’s drive from here, so every night we would drive her so she could do the show and bring her back after. My wife and I split it up, but I saw the play about 23 times, [laughs] and a lot of times I would draw during it. I’m making a book about it because I thought a lot about the play. I will draw during TV shows, during plays, I’ll draw while I’m driving sometimes, at stop lights.

This constant activity of drawing, again, is a way of looking. When I go to art museums I definitely draw the paintings and things that I see, because it really makes me look. Drawing is a way of interfacing with the world. With the TV stuff and Project Runway, I watch a show I like so I draw it. I actually have a bunch of drawings from the new Blade Runner movie that I did while I watched it, which I really liked. I usually have really bad taste in films and TV shows, anyway. I did some Lost drawings, I drew part of the first episode – actually, it got published somewhere – because that first episode was so magnificent, so crazy. Perfect. At my old job I did trading cards for TV shows and movies, and I did them for Lost – for the first four seasons of Lost I have all these trading cards that I made.

When I first started doing the poetry comics work, there were only a few other people out there, less than there are now. It’s cool to see that there are more and more people understanding where we were coming from and being a part of it. I’m not saying that they are inspired by us, nothing like that, but it’s more that they are coming to the same conclusions that we came to, about how this stuff could work. It’s been great to see that. And so much good work is being made. I did a project with a German poet, Lydia Daher where she sent me poems and I would do drawings for them, and then the German museum she was working with made a book out of it.

What she sent me was in German, and then two different English translations, so I think the idea was that I’d pick the translation that I wanted, what I did was I drew everything. So I drew a drawing for a stanza of the German part and then I drew the same drawing a little different for each of the English ones. I thought a lot about translation, but also I was very flattered that she wanted to work with me, her work is great and the way that they printed the book is amazing. Almost nobody has seen it over here, because I don’t have that many copies of it and [laughs] I don’t really know what to do with it.

That never bothered me, that the stuff that we all do is way out there, with a small audience. I guess I find the value of making this stuff, and then also in seeing it again later, and less in glory, riches and fame. For all I know, there really are none in this racket. [laughs] To me it’s funny that I spent two decades making this sort of poetic comics work, and it’s the Trump project that’s been my first big, printed work published by somebody else. I’ve had some smaller things printed that were really good and that I’m really proud of, but it’s funny that this is a big thing. For now, anyway.

Visit Warren’s website to see more of his work, and buy his books!

To comment, please send an email to submissions@uncomics.org.

Any comments may be subject to publication on this site only. Your contact information will not be shared with third parties.