The odradek of it all: Transcript

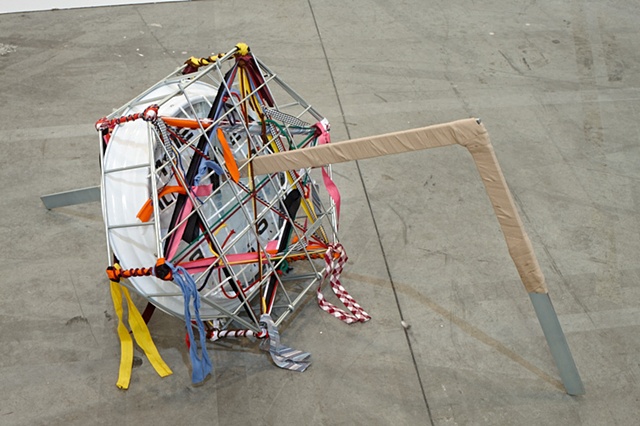

This is a transcript of the Uncomics podcast’s first season finale. To listen to the episode instead, please visit the episode post. Main image: Per-Oskar Leu’s sculptural rendition of the odradek, 2011.

Intro

Welcome back to the Uncomics podcast, where I’ve talked to some of the finest artists working in the intersection between contemporary arts and comics right now.

For the season one finale I wanted to gather some of the common threads from the talks I’ve had through this “online symposium”, apply them to my rudimentary framework and attempt to draw a picture of sorts, of where these conversations may lead us in future seasons.

As my notes grew I realised that this would be too much of my monotonous droning to expect anybody to sit through. Instead, since I’ve now procrastinated well into the festive season, let me finish off by telling you a story.

Yes, I’ve been down on stories and narrative when discussing uncomics throughout this season, but borrowing from a master of the ambiguous and the liminal, I think we’ll be in good hands.

My name is Allan Haverholm, and this is Uncomics – the Kafka session.

The cares of a family man, by Franz Kafka

Some say that the word Odradek comes from Slavonic and they try to prove the formation of the word on the basis of this. Others believe that it originated in German and was only influenced by Slavonic. The uncertainty of both interpretations, however, rightly leads to the conclusion that none of them is correct, especially since neither can be used to find a meaning for the word.

Of course, no one would bother with such studies if there weren’t really a being called Odradek. At first it looks like a flat star-like spool for thread, and indeed it seems to be covered with twine; however, it is probably only torn pieces of string of various kinds and colours, old ones knotted together, but also twisted into each other. However, it is not just a spool, but from the centre of the star a small cross-rod emerges and then another rod is attached to this rod at right angles. With the help of this latter rod on one side, and one of the radiations of the star on the other, the whole thing can stand upright as if on two legs.

One would be tempted to believe that this structure had formerly had some purposeful form and that now it was only broken. But this does not seem to be the case; at least there is no sign of it; nowhere are there any rudiments or fractures to be seen that would indicate anything of the kind; the whole appears senseless, but complete in its own way. It is impossible to say anything more about it, because Odradek is extremely nimble and cannot be caught.

He lurks in the attic, the staircase, the corridors and the hallway by turns. Sometimes he is not to be seen for months; he has probably moved to other houses; but then he inevitably returns to our house. Sometimes, when you step out of the door and he is leaning against the banister, you feel like talking to him. Of course, you don’t ask him any difficult questions, but treat him like a child - his tiny size alone moves you to do so. “What’s your name?” you ask him. “Odradek,” he says. “And where do you live?” “No fixed abode,” he says, and laughs; but it is only such a laughter as can be produced without lungs. It sounds something like the rustling of fallen leaves. That is usually the end of the conversation. Even these answers are not always forthcoming at that; often he is silent for a long time, like the wood he seems to be.

In vain I ask myself what will happen to him. Can he die? Everything that dies has had some kind of goal, some kind of activity beforehand, which has ground away at it; that is not the case with Odradek. So will he one day roll down the stairs at the feet of my children and my children’s children, dragging ends of thread behind him? He obviously harms no one, but the idea that he should outlive me is almost painful to me.

Carman Cicero, Odradek (1959). Photo: Guggenheim

Interpretation

I find the odradek of Kafka’s story endlessly interesting. On a very basic level, the family man narrator is terrified by this creature-thing that squats in his house, yet can’t be fully described in terms and concepts available to him. It’s precisely because the odradek evades etymology, taxonomy and categorization that the narrator cannot let it go, but can’t accept it either.

And I personally recognise the look of the same fundamental confusion on people’s faces when I explain uncomics. It seems to alienate them that I consider comics a phenomenon that settled just a bit to soon, and that I want to open it up for new interpretations? Even though uncomics is just a different perspective on a commonplace phenomenon, the concept seems to not make comics excitingly peculiar to them the way it does for myself — it repels them to see comics as anything but what they already know.

There are several ways that I see the odradek as a mental image of uncomics but, characteristically, none of them fit entirely because Kafka’s description of the odradek opens itself to ambiguity and away from textbook definitions. Most analyses that I’ve come upon in preparation for this episode focuses on the disruptive nature of the odradek, its tendency to deflate conventional expectation, to the point that it even trips up explicit interpretation.

Different writers see it either as a rejection of the bourgeois society morés represented by the family man of the title, the patriarchal Hausvater, or as an allegory of Marxist concepts of the commodity. The more psycho-analytically minded, from Freudians through Lacan to Zizek, tend to see the odradek as the castration of the narrator — but I would like to go a little deeper into one different take on the meaning of The cares of a family man —

Kafka scholar Malcolm Pasley points to an interesting snippet from Kafka’s correspondence with his friend and later executor, Max Brod. Writing about a different short story, Elf Söhne, or Eleven sons, he says that “it is really about eleven stories that I’m writing at the moment”. That is, Kafka would use his writing as a space to conceptualise and figure out his own creative process. Not unlike, perhaps, how an artistic researcher needs document their process in order to synthesise practice and theory — or how some of my guests in this first season reflect and build on their own previous work with each progressive step.

But where this method of self reflexion comes to bear on the story at hand is in their shared context. Eleven sons was published in the 1919 collection Ein Landarzt, or A country doctor, along with the eleven stories that the author wrote it about — and two more, including The cares of a family man. Having trawled through Kafka’s personal writings of the period — drafts, correspondence and diaries — Pasley concludes that this story, too, is a meta-cypher about the writer’s creative struggles with another, unpublished piece called Der Jäger Gracchus.

I’m sure any creative listening will recognise in Kafka’s description of the odradek a not fully formed concept that comes and goes, only teasing its purpose and nature with sparse, bewildering statements. That frustrating stage of creation where “the whole appears senseless, but complete in its own way” yet never seems to find a cohesive form. When Kafka describes the odradek’s laughter as “the sound of fallen leaves”, he might as well be talking about the sheets of paper he filled drafting a story to no avail.

Even so, the narrator’s voice echoes the writer’s as he ponders this idea that remains too nimble, too slippery to be caught or fixed, and in that frustrated flux the odradek comes instead to represent a productive obstruction, what some artists have called “a pebble in their shoe”. Because although Der Jäger Gracchus remained a proverbial white whale for Kafka in his lifetime, the irksome process birthed instead The cares of a family man. Similarly, whether they are own works or those of others, such obstructive pebbles in an artist’s shoe can provide much food for creative thought. Call it the riddle of the sphinx, or a Buddhist kōan that keeps generating new answers and new questions, like a perpetuum mobile.

Barring the consternation of a work that will not conform to the idea and mental image one might have imagined for it, this echoes what many of my guests on the Uncomics podcast have talked about. Rosaire Appel’s resistance to complacency and doing the same thing for too long; Warren Craghead’s idea of “fun trouble” and stealing from other artists, or Simon Russell’s insistence on a sense of play in the creative process: all of them reflect differently in the notion of the creative conundrum, just as the odradek has launched a thousand theses.

An early Kafka scholar, Walter Benjamin, would define a pattern of “cloudy spots” in his works, points of disturbance that “cannot be appropriated by language or interpretation” (Newman, M. p.2). Again, the odradek seems an obvious case, but I shall try to appropriate it a little further.

Benjamin, of course, is better known for his essay on The work of art in the age of its mechanical reproduction (1935), but perhaps also for his unfinished Passagenwerk, or Arcades project, named after the arched side streets and alleyways of Paris. Those were passages off the main streets where 19th century flâneurs and dandies might drift purposelessly through the metropol, browsing flea markets and trinket stores. Benjamin’s interest lay as much in such bargain bin remnants of times past, “surrealist objects” that break chronology as they change hands much later. Like the odradek, they had formerly had purposeful form but now, out of time and context seemed either broken or extraordinary.

If we wanted, we could attribute particular meaning to certain details of the odradek’s description. It reminds the narrator of a spool or spindle, likely because of the pieces of thread that hang from it, but perhaps also because he wants it so intently to have or have had a purpose. Our family man is a utilitarian, after all, and finding the odradek lacking in most things that he values, he treats it “rather like a child”. Could it be perhaps that the arrangement of intersecting rods and twine that makes up the creature is in fact more like a toy? Or at least it might look like one to such a serious, responsible grown-up as the father of the house.

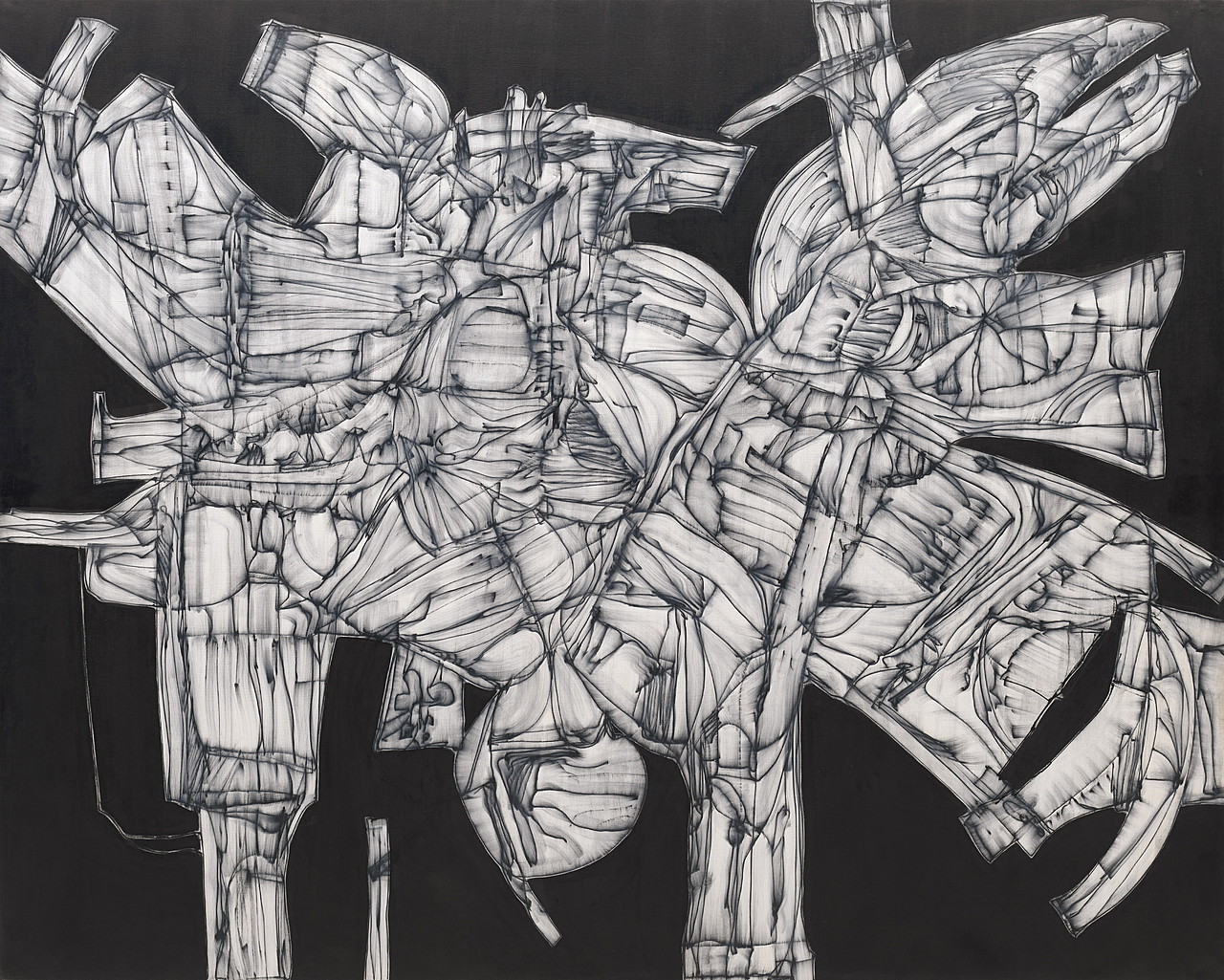

Judith Scott, Untitled (2000). Photo courtesy of Creative Growth Art Center.

I have already suggested that the odradek has to do with play and creativity, but then, I’m much less grown-up than he. I might even claim a similarity to the way comics have historically been viewed as children’s books! But I lose my thread. Perhaps I will hang onto some of the odradek’s instead. Find my way through this maze of arguments I’ve built up.

But Ariadne’s lifeline out of the Minotaur’s labyrinth is only one way to think of narrative threads. I’ve brought up Donna Haraway’s image of the ever changing string figures several times in our artist talks this season. Barbara Stafford, in her Visual analogy, talks rather of combinatorial weaves — “a tapestry of interwoven patterns” (Stafford, p. 141) — webs of relation, knitting and braids than of throughlines.

When I talked to Erin Curry, a silk spinner as well as an uncomics artist, I hoped she would play along with that visual analogy, but she is of course concerned with exploring ephemeral landscapes — spaces as much as planes, lines or single points. Her truck is as often with the explorers and travellers who left their fixed abode to expand upon the maps of the known world.

And the odradek is an itinerant too, only covered in “torn pieces of string”, suggesting a relation to yarns but not tethered by them. Occupying “the attic, the staircase, the corridors and the hallway”, it travels the liminal spaces between and outside proper rooms, not unlike the proto-Situationist flâneurs that drifted through Walter Benjamin’s Parisian passages, uncharted desire paths connecting the main roads.

In other words, the odradek is a creature of the in-between — the margins and gutters — where we may suspend conventional, linear reading and make associative leaps of faith or logic to arrive at unexpected destinations. In a comics context the in-between does not simply dissect but underlies the page as a map-like structure, a manifestation of Benjamin’s “cloudy spots” in its simultaneous splitting and merging of the base image units. Where Scott McCloud triumphantly jumps to the conclusion that “comics are closure!” (McCloud, p. 67), I only modestly suggest that the odradek is one way to look at uncomics.

And the artists I’ve spoken to in this first series of the Uncomics podcast, and the ones featured in the Uncomics anthology all navigate another liminal space where definitions blur and overlap — the no man’s land where the porous peripheries of comics and contemporary art cross pollinate. Where their asemic marks, found objects, and wearable sculptures suggest rather than signify ambiguous story forms that refuse to be nailed down by a prematurely settled taxonomy of comics.

Conclusion

And with that idea of comics as a stunted form we are back at the reasoning I laid out in the very first episode of the podcast, that we agreed a bit too soon upon what comics are, and from too narrow a test sample.

Rather than remaining an open inquiry into its own potential — in relation to and mutually influencing other art forms — by the early 20th century comics was closed around itself as an entertainment domain, by an industry that saw no profit in experimental forays into the contemporary arts of the time.

I’ve skimmed through examples of how Kafka’s ambiguous figure of the odradek can be considered, in different perspectives, as unending process; as material that cannot be processed except as a creative conundrum or obstruction; and finally, as a site of ambiguous superposition that we might see reflected in the branching liminal structure of comics layouts.

More than anything, it is the indeterminate nature of the odradek that appeals to me, the keen sense of flux with which Kafka characterises, but conspicuously falls short of fully describing the creature-thing. It is because he only provides fragmented and contradicting information that the mental image of the odradek is not allowed to settle, and indeed becomes fundamentally un-settling both to the narrator and the reader. Because neither the odradek nor uncomics care much for established assumptions that would tie them into well-known structures and patterns. Dressed only in fragments of such structures, they both open up toward and reveal the great unknowns that we fail to realise when we work from false premises.

Nairy Baghramian and Katinka Bock, Odradek (2018). From the 2018 “Odradek “ group exhibition at Malmö Konsthall. Photo by Helene Toresdotter

A hundred years on, the odradek figure still inspires new interpretations, even in fields that Franz Kafka may not have given serious thought when he wrote Die Sorge des Hausvaters, in the last years of World War One. As this first podcast season, and the Uncomics print anthology has demonstrated, however, the general, linear narrative perception of comics is as rudimentary and insufficient as the short story’s initial attempt at a thesaurus entry for “odradek”.

To continue exploring uncomics, then, means to embrace ambiguity and open-ended process rather than neat and final results. To preserve the superposition where the cat remains both dead and alive, as it were. Uncomics as a multidisciplinary field of research must remain nimble and difficult to catch, because it exists in the tension between separate, constantly evolving art forms. Claiming a conclusive definition to such a fluctuating, amorphous field would be a sign of delusion worthy of the story’s family man.

It is more constructive to think of uncomics as the works of artists responding to unstable and changing society norms and structures by engaging with uncertainty and ambivalence on a structural level in their uncomics. And if uncomics constitutes a disruptive element to our concept of comics in general, perhaps they can also cause some productive trouble in the industries that have shaped those concepts. Having emerged on the margins outside the comics mainstream, and still not settled, perhaps the artistic field of uncomics could be an apt form of expression for the actually marginalised?

Those are questions for future research, of course, as the first leg of the podcast reaches its end. There is much yet to be explored, much ground to cover both here and on the Uncomics website, and it goes without saying that I will be posting there while I prepare the next season of podcast interviews. Since the field is so deliberately broad, and the avenues of inquiry so branched and faceted, things will probably get weird now and then, and — as you may guess after this last half hour’s talk — I say that as a promise, not a warning.

Outro

Thank you for listening to the Uncomics podcast! The entire first season is now available for download at uncomics.org, or through your podcatcher of choice.

I recommend that you subscribe or listen via the website uncomics.org and its RSS feed. However, the show is available through iTunes and Google Play as well, and if reviews are very much appreciated. That shouldn’t stop you from recommending the Uncomics podcast to friends and colleagues through other channels like word-of-mouth in real life or on your social media. All virality is appreciated!

I aim to keep this podcast free of advertisements and commercial interests, but you can support the Uncomics project with a small recurring donation on Liberapay: Go to liberapay.com/uncomics to set it up safely using your preferred mode of payment.

These talks are just the beginning of the conversation. If you have feedback, questions or your own perspective on the subjects my guests and I have touched upon in this series, please email podcast@uncomics.org

On uncomics.org you will also find galleries and profiles of my guests, the Uncomics mission statement and print anthology, and more material about art, comics, and their fertile common ground as the podcast and site grow.

The Uncomics podcast is produced and hosted by me, Allan Haverholm. Theme and incidental music by Allan Grønvall Pedersen.

Franz Kafka’s original story, Die Sorge des Hausvaters, is in the public domain. My German skills being what they are, I translated it for the purpose of this episode using the online machine translator Deepl, but compared the results to official translations by Willa and Edwin Muir, Anya Meksin, Stanley Applebaum, and Malcolm Pasley to ensure it was accurate.

Further reading

- Benjamin, W. (1929) “Surrealism: the last snapshot of the European intelligentsia”. In Critical Theory and Society A Reader (pp. 172-183). Routledge.

- Doležel, L. (1984) “Kafka’s Fictional world”, Canadian Review of Comparative Literature, 11(1), pp. 61–83. Available at: https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/crcl/index.php/crcl/article/download/2640/2035

- Lucht, M. and Yarri, D. (eds) (2010) Kafka’s creatures: animals, hybrids, and other fantastic beings. Lanham, Md: Lexington Books.

- McCloud, S. (1994) Understanding Comics: The invisible art. HarperPerennial. New York: Harper Collins.

- Newman, M. (2017) “Odradek and the rethinking of political method in the work of art”. 4th Biennial Conference of the International Walter Benjamin Society, Worcester College, University of Oxford, United Kingdom. Available at: http://research.gold.ac.uk/21412/

- Oki, M. (2018) “Hearing/seeing dread: thought of distortion and transformation in Kafka’s The Burrow and Odradek”, Journal for Cultural Research, 22(1), pp. 16–26. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14797585.2017.1382233.

- Pasley, M. (1971) “Kafka’s Semi-private Games”, Oxford German Studies, 6(1), pp. 112–131. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1179/ogs.1971.6.1.112.

- Powell, M. T. (2008) “Bestial Representations of Otherness: Kafka’s Animal Stories”, Journal of Modern Literature, 32(1), pp. 129-142. Available at: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/257974

- Schwab, G. (2016) “Phantasms of the Mutated Body: Kafka’s Critique of Anthropocentric Reason”, Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai - Dramatica, 61(2), pp. 91–102.

- Stafford, B.M. (1999) Visual analogy: consciousness as the art of connecting. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Willumsen, N. (2010) Reading Kafka: or, If You Find Odradek, Kill It. Undergraduate Thesis, Bachelor of Philosophy. The University of Pittsburgh. Available at: http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/7747/1/willumsennc_etd2010.pdf

To comment, please send an email to submissions@uncomics.org.

Any comments may be subject to publication on this site only. Your contact information will not be shared with third parties.